CHAPTER 5

Demographics

Population size is the most important determinant of national power. With it, a lack of other determinants of power can be overcome. Without it, great power status is impossible.

We’ve already looked at the fundamentals of human reproduction, and how the evolution of big brains and bipedalism drove the development of pair-bonding, romantic love and the family. In this chapter, we’ll look at the bigger picture: how human populations shaped our history.

Compared to our closest evolutionary cousins, the other species of great apes – chimpanzees and bonobos, gorillas and orang-utans – humans have a remarkably slow life history. We saw in Chapter 2 that human children need a long period of development after birth before they no longer depend on their parents for survival. Even after infancy, humans take a long time to reach sexual maturity and begin their own reproductive lifetime. This period of adolescence – our teenage years – is far longer in humans than any other great ape. In foraging societies, on average, females start to reproduce at the age of 19, compared to 10 in gorillas and 13 in chimpanzees.1

While we are very slow to start reproducing, humans are exceptional in how frequently females can give birth. The average birth interval in traditional hunter-gatherer societies is around three years – significantly shorter than the four-, five-and-a-half- and eight-year intervals for gorillas, chimpanzees and orang-utans, respectively.2 Our ape relatives are therefore caught in a demographic dilemma: their birth rates are barely greater than their death rates and so their populations can grow only very slowly.3 Not only do humans have a comparatively huge reproductive potential, but human babies are much more likely to survive to reproductive age than their chimpanzee cousins.4 So what are the secrets of our demographic success?

As we saw in Chapter 2, humans are a species of persistent cooperators. This is also apparent in the way we breed. Humans raise their offspring within a social system known as cooperative breeding, where members of the group care for children that aren’t their own. As a reproductive strategy, this is pretty rare in nature: in only about 3 per cent of bird or mammal species do individuals other than the parents help raise the young. It occurs in some primate species, but in none of the great apes other than us humans. In traditional human societies, childcare is shared among siblings, as well as the wider family. In particular, as human females have great post-menopausal longevity, grandmothers past their own reproductive lifetime are able to support the younger generations of their family.

Humans are generous not just with their time lending a helping hand with childcare, but also in sharing food. Mothers with a young baby are hit with a double whammy. While still nursing they not only need a higher calorie intake to support the breastfeeding but also don’t have enough time or energy to forage for food (to provide this additional nutrition for themselves and their older children). Food sharing therefore makes a huge difference to her reproductive capability. Adults also readily share food with the juveniles in the group who aren’t yet able to forage enough to be self-sufficient. In other apes (and indeed most other mammal species), parental care stops with weaning; after that a juvenile becomes independent and is responsible for finding its own food. Humans developed a different strategy: infants are weaned early, but then their food intake is effectively subsidised for several more years by those around them. In traditional hunter-gatherer societies, a human baby is weaned at the age of three – but already at the age of one in industrialised societies, aided by dietary supplements and bottle feeding.

And it’s not only other adults, such as the father or grandmother, who contribute extensively to supporting the mother with her child-rearing. Older children help support their family by contributing foods that are more easily available, such as fruit or small animals, or helping out with the less strenuous farming tasks in agricultural societies. And they assist with the crucial processing of raw food before it can be consumed – which helps make the nutrients more digestible or preserves them for longer – such as pounding, soaking and cooking. Or they collect firewood and fetch water, which are chores that can take several hours every day. Thus by the time a mother has two or three older children, the task of raising further offspring actually gets easier.

Compared to our ape cousins, who can raise only one child at a time to independence, cooperative breeding, food sharing and not least biparental investment in childcare means human mothers are able to increase their reproductive output by stacking up a chain of overlapping juveniles, relying also on the support of the elder children to help feed and support the youngest. And it is for this demographic superpower – the rate at which we can grow our population – that humans are an absolutely remarkable ape.5

But while we exhibit a much greater reproductive growth rate than other great ape species, there have been profound differences in demographic potential between different populations of humans. Most notably, the development of agriculture over ten thousand years ago created an enormous shift in human demographics.

For most of the history of civilisation – before the advent of modern machinery, artificial fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides – agriculture invariably demanded back-breaking labour. Agriculturalists had to clear forest to create farmland, manage the land by ploughing or maintaining irrigation canals, and then sow their fields, nurture the crops and weed out other plants. The harvest of cereal crops requires reaping, threshing and winnowing, before storing the grain and finally milling it for consumption. Pastoralists keeping livestock were able to exploit natural plant growth for grazing but still had to invest a lot of time herding their animals, defending them from predators, and preparing fodder for the winter.6

Agriculture also exposes its practitioners to a number of health problems and subsistence risks. Eating a lot of grains creates more wear and tear on our teeth, and the focus on carbohydrate-rich foods promotes dental decay.7 There is also a higher risk of malnutrition from relying on a small range of domesticated plants and animals. Even more acutely, while hunter-gathers are flexible eaters, roaming over wide areas to access a great diversity of edible wild plants – including roots, tubers, berries and leaves – at different times of the year, a farming population quickly faces famine if its staple crop suffers harvest failure. And as we saw in Chapter 4, agriculturalists are more exposed to transmissible diseases from living in close association with their livestock, and cheek to jowl with large groups of other people.8

But all that being said, farming can yield a greater return of food than foraging. All the effort invested in tending the land and crops means that an acre of farmland provides much more nutrition than the same acre of forest or wild grassland, and herding livestock is a more efficient way of deriving meat and other animal products than hunting wild game. This agricultural surplus can be stored from one year to the next and also free up labour for other occupations not focussed on food production, such as specialist craftspeople, leading to the development of more complex technology and social organisation.9

It has been generally accepted that agricultural societies can support a faster birth rate than hunter-gatherer societies, and so their populations grow more rapidly. It has been argued, for example, that sedentary farming societies can have babies in quicker succession because they don’t have to carry their infants long distances, as do forager groups roaming between different camps. More recent archaeological studies, however, have suggested that the long-term population growth rates of some hunter-gatherer societies could match that of prehistoric agriculturalists in both the Old and New Worlds.10 But this is only up to the carrying capacity of the land, which is lower with a hunter-gatherer lifestyle than an agrarian one.

So even if agricultural food production doesn’t necessarily sustain a faster population growth rate, the fact that farming yields more nutrition from the same area of land means that it can support greater total population numbers. And when a particular area becomes too crowded with arable farmers or herders, and the carrying capacity of the land is maxed out, large numbers of people begin dispersing outwards to settle surrounding areas. The irony of agriculture, with its sedentary lifestyle rooted to a particular patch of land, is that the demographic pressure created by increasingly dense populations pushes farmers ever onwards to displace hunter-gatherer communities.

THE BANTU EXPANSION

Africa is truly enormous. It covers an area almost as big as the continents of Europe and North America combined, with a huge variety of environments and peoples – indeed, there is more genetic diversity among the people of Africa than within the whole rest of the human species around the globe. This is a consequence of our long evolutionary history within the continent, before a small population migrated out of Africa during the last ice age and populated the rest of the world. It’s all the more surprising, then, that sub-Saharan Africa is astonishingly uniform when it comes to the languages spoken; this vast continental region is much less linguistically diverse than Asia or pre-Columbian America.

The majority of sub-Saharan Africans today – more than 200 million people – speak a tongue that is part of a tight-knit group of around 500 closely related languages known as the Bantu family.11 This particular language family appears to have emerged around 5,000 years ago in a region of western Central Africa that now straddles the border between Nigeria and Cameroon, from where it spread rapidly to cover most of the central, eastern and southern areas of the continent. Separate languages gradually developed and transformed as they propagated – shifting in their pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar – so that today we find a branching family tree of Bantu languages draped across the sub-Saharan continent, with the stem rooted in tropical West Africa.

The rapid spread of this language family across sub-Saharan Africa is known as the Bantu Expansion. Its staggering scale is perhaps best grasped by comparison. The Bantu family is just one of 177 language subgroups within the wider phylum of Niger-Congo languages.12 It is equivalent to, for example, the Nordic (or North Germanic) branch of languages – spoken in Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Iceland – within the whole Indo-European language phylum that extends today in two broad swathes: across Europe and Russia; and from Iran through to northern India.13 But whereas the Nordic languages are only spoken in one small corner of the sprawling patchwork quilt of the different tongues of Europe, the Bantu family extends across 9 million square kilometres of sub-Saharan Africa.14 It’s as if the whole of Europe spoke close variants of the same language.

So, you may wonder, why did so many people across such a huge area all come to speak the same small family of languages? What drove the rapid expansion of this language family? Did the original Bantu-speakers perhaps exhibit military prowess that enabled them to drive a determined campaign of conquest across the continent15 (akin, for example, to the cause of Spanish prevalence in Latin America today)? Or if the interaction between populations wasn’t violent, did a large group of incoming Bantu migrants completely replace or interbreed with a pre-existing population? Or did the Bantu languages spread not through population movement but by a process of cultural diffusion, whereby a custom or technology is progressively transferred from one group to its neighbours?

Sometime around 4,000 years ago, Bantu-speaking peoples began dispersing out of their homeland on the border between modern-day Nigeria and Cameroon.16 This migration proceeded along two main routes. One branch headed south from the ancestral lands before bearing eastwards across the equatorial rainforest into East Africa, and then down towards the southern tip of the continent. By about 2,500 years ago, Bantu-speaking people had reached Lake Victoria in East Africa and mastered iron toolmaking technology,17 before expanding further inland.18 A second major migration pathway bore southwest along the coastal plains,19 and by around 1,500 years ago, Bantu-speakers had spread as far as Southern Africa.20 Genetic studies indicate that this expansion didn’t proceed as one smooth, continuous diaspora, but in fits and starts in successive phases of expansion,21 like ripples of migration lapping over one another.

What’s more, when the Bantu arrived in new locations, they not only brought with them their way of speaking but also introduced new technologies. The earliest stages of the expansion through the equatorial rainforest are associated with the proliferation of villages and sedentary living, as well as the appearance of pottery and large polished stone tools – in particular axes and hoes.22 After this initial phase, the Bantu Expansion also spread agriculture and metallurgy. The Bantu-speaking cultures cultivated a set of very productive crops, including staple cereals such as pearl millet, as well as pulses, yams and bananas; and they kept domesticated guineafowl and goats,23 all of which enabled them to support dense populations.fn1

The genetic analyses of populations across sub-Saharan Africa have illuminated the past movements of the Bantu peoples during these major migrations.26 Most notably, within Bantu-speaking populations today there’s a great deal less diversity in the Y-chromosome DNA, which is transferred solely from father to son, than there is within the mitochondrial DNA passed from mother to children. This suggests that the Bantu languages were spread mostly by migrating men, who then interbred with indigenous hunter-gatherer women – possibly in polygynous relationships.27 And there wasn’t just mixing of genes between the indigenous populations and the incoming Bantu migrants; some aspects of local hunter-gatherer languages were absorbed into Bantu linguistics. For example, several Bantu languages in Southern Africa have adopted the consonants made of clicking sounds from the Khoisan tribes.28

What has become clear in recent years, therefore, is that the Bantu Expansion was not just the diffusion of languages, but the spread of an entire cultural package – language, agricultural lifestyle and technologies – carried by the physical migration of Bantu farmers. Farming produced an abundance of food, pottery allowed surpluses to be stored and cooked, and iron tools made possible the more effective clearing of the land. A stationary lifestyle supported by crops and domesticated animals allowed for greater population that drove the expansion onwards into new territories occupied by hunter-gatherers.

Thus, the astonishing extent of the Bantu languages across Africa today is the conspicuous relic of one of the most dramatic demographic events in human history.29 Other large-scale language dispersals have occurred in the last 10,000 years, such as the spread of Austronesian-speaking farmers through Polynesia and Micronesia, but the Bantu expansion is utterly remarkable for its sheer scale and pace. The second stage of the Bantu Expansion, over 4,000 kilometres from central Cameroon to Southern Africa, took less than two millennia – a staggering rate for population dispersal.30, 31

After the domestication of wild plant and animal species around the world over ten thousand years ago, agricultural societies expanded into new territories, interbred with the native populations and replaced the original hunter-gatherer lifestyle with arable farming or pastoralism. Ultimately, farming came to displace foraging over much of the world, largely driven by demographic factors – farming supported greater population densities (and perhaps a more rapid growth rate) and powered expanding migration waves. As agriculturalists spread, they carried with them not only their agricultural way of life, but also languages and technologies.

MILITARY MIGHT

Once non-nomadic agriculturalism and then cities became established, demographic trends continued to influence the history of civilisation and the battle for power between settled states. For a while, small states such as Venice and the Netherlands were able to break the dependence of both economic and military strength on population numbers by operating lucrative maritime trading empires and paying mercenaries to fight their wars. But in general, the military strength of states has been directly tied to their population size and the number of fighting-age men.

This is not to deny that other factors play a role in war – the training of troops, the terrain of the battlefield or the tactical brilliance of a general. Sometimes, a new military technology serves as a ‘force multiplier’, increasing the effectiveness of one side’s soldiers on the battlefield and tipping the balance. At times, such innovations have shattered the equilibrium between powers, resulting in the collapse of long-established civilisations and empires and a reconfiguration of the world order. But invariably, any new technological advance – whether that is the chariot, the iron blade or the gunpowder firearm – and the tactical advantage it bestows, is before long acquired by competitors, and the balance of power is restored. Armed conflicts once again become primarily determined by the weight of numbers.

Across the millennia, the key to military success was simply to command greater forces on the battlefield. There have been exceptions to this rule of course, when a smaller force was able to achieve victory against the odds. Such David and Goliath encounters include the Battles of Marathon (490 BC) and Agincourt (AD 1415), and more recently the Six-Day War (1967). But underdog triumphs are few and far between in history.fn2

It goes without saying that larger populations yield larger armies. And so by extension, the more populous states tend to prevail with the outbreak of armed conflict, either as the invaders or defending their own boundaries against aggressors. Smaller states tend to get overpowered and absorbed by larger states. And of course this process can snowball. The state able to field the larger army defeats its neighbours and brings those territories under its own dominion. With control over more land and more men, the stronger state can conquer and absorb more and more adjoining territory. Provided this state is able to maintain internal stability and supply a swelling army under one banner, it can continue to expand across larger and larger regions. Thus is the birth of empires.

From the days of clashing tribes, through the civilisations of antiquity and medieval kingdoms mustering their armies, to modern total war, overall population size has often proved decisive. The men marching into battle are only the point of the spear: it is an entire society that supports an army. Beyond the carpenters and cooks that moved with the soldiers on campaign, people at home made weapons and armour, bred and trained horses, constructed wagons or chariots, and worked in the fields to feed the army on the march. Of course, through much of history, the young, able-bodied men mustered into an army were the same needed to tend the fields at home. For millennia, therefore, there has been a seasonal pattern in the pulse of wars. Campaigns tended to avoid the harsher weather conditions of winter, and were usually launched in spring or autumn, so as to keep labourers in the fields for the most intense phases of the agricultural cycle, such as harvest.32 In the twentieth century, the advent of total war saw mass conscription and the mobilisation of the entire civilian society for the struggle, which included women and older men working in armaments factories.

This dominance of demography in warfare has not escaped military thinkers and philosophers. The sixth-century BC Chinese general and strategist Sun Tzu advised in The Art of War: ‘If your enemy is in superior strength, evade him.’ In the first century AD, the Roman historian Tacitus was concerned by the small sizes of Roman families compared to those of the rapidly breeding German barbarian tribes beyond the borders.33 An early-nineteenth-century proverb propounded, ‘Providence is always on the side of the big battalions.’34 And the Prussian general and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz wrote in his study On War (1833) that the superiority of numbers is ‘the most general principle of victory’.35

The number of men bearing arms on the battlefield depends on the number of babies in the cradle two or three decades earlier.36 And so the military might of a state rests on fundamental demographic factors such as birth rate. Unsurprisingly, therefore, states worry about their population growth and display mounting anxiety when the birth rate slows. This is what happened in France in the nineteenth century. For centuries, the country had supported the largest population in Europe, but that changed with the legacy left by Napoleon.

DEMOGRAPHIC EFFECTS OF NAPOLEON

Napoleon was undeniably a brilliant military tactician and accomplished statesman. Born into a lowly background, and riddled with insecurities, he was obsessed with his own prestige. He seized power from the leaders of the fledgling French revolutionary republic in a bloodless coup in 1799 and installed himself as the head of a more authoritarian regime. He made himself emperor in 1804 and set about reforming France’s military, financial, legal and educational institutions. He left a vast legacy, not just within France but across Europe and around the world. Ultimately, it was his insatiable ambition and hubris that led to his downfall, which began with the ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812. His Grande Armée, the greatest military force the world had seen, was swallowed by the freezing expanse of the Russian hinterland on the retreat from Moscow.37

Overall, around one million French soldiers died in the Napoleonic Wars of 1803–1815 and perhaps a further 600,000 civilians from the hunger and disease caused by conflict.38 This represents almost 40 per cent of the conscription class of 1790–1795, and is a greater proportional loss even than that suffered a century later when France hurled its young men against imperial Germany in the First World War.39

A great number of young Frenchmen never came home, and this, coupled with the general disruption of war, caused a significant temporary drop in the birth rate. But long after the immediate effects of military conflict, throughout the nineteenth century, France continued to experience a very slow population growth, falling behind other European nations. This is partly due to the fact that France was slow to industrialise and remained a predominantly rural population with low living standards.40 The decline in Roman Catholic observance after the revolution may also have contributed to smaller families.41 But perhaps the main reason for the sluggish population growth was another legacy of Napoleon’s rule.

Under the Ancien Régime, French law had been a patchwork of differing customs and rules across the provinces of the country; it was also riddled with special exemptions and privileges granted to the aristocracy by kings and lords. After the revolution, these last vestiges of the feudal system were abolished and fresh legislation was instated in accordance with the core tenets of the new republic: liberté, égalité, fraternité. When Napoleon seized power in 1799, he set about overhauling the French legal system from the ground up into a single, codified set of laws. The French Civil Code was crafted by a commission of jurists overseen by Napoleon himself and was enacted in March 1804. It became known, after its creator, as the Napoleonic Code.

Of particular concern to the post-revolutionary lawmakers was the overhauling of the old laws on inheritance that had enabled the dynastic transmission of wealth and power within feudal and aristocratic systems (as we explored in Chapter 2). These relics of the Ancien Régime were wholly incompatible with the ideals of the new republic.42 Egalitarian principles for inheritance were already established prior to Napoleon. The National Assembly had decreed the abolition of primogeniture in 1791 and, by 1794, established the convention that the testator could only dispose 10 per cent of their property to a chosen heir, with the rest divided equally among all offspring regardless of sex or birth order.43 But it was Napoleon who enshrined partible inheritance as articles within his codified civil law. And crucially, the Napoleonic Code also increased the disposable portion of inheritance the testator was free to choose to whom to bequeath it. Article 913 of the code specified that if a father had only one child, he could choose how to disperse half of the inheritance, with the rest going by law to the child; with two children he was allowed to decide what to do with one-third of the total legacy; and only one-quarter with three or more children.44

And this is where the demographic problem had its roots. While the motivation for crafting an egalitarian society was laudable, the inheritance provisions of the Napoleonic Code – the combination of enforced partible inheritance among all children along with a freely disposable portion based on the number of children – inadvertently created a strong incentive to have smaller families. With fewer children, the testator was allowed a greater disposable fraction of his total legacy and so was better able to prevent the dilution of family assets into the next generation.

France had for a long time been the most populous country in Europe. During the Middle Ages, more than a quarter of the continent’s total population was French.45 At the end of the eighteenth century, when Napoleon seized power, France still had the second-largest population in Europe (after Russia), with around 28 million people.46 This was around 10 per cent more than the states that would come to be unified into Germany, and more than double that of Britain.47

Although, before 1800, marital fertility in France was similar to that of other European countries, the birth rate declined rapidly as the century wore on48 – from around 30 live births per thousand people in 1800 to around only 20 by the middle of the century. By comparison, over the same period, the German birth rate fluctuated at around 37 births per thousand people, whereas in Britain it peaked at over 40 in 1820, before levelling off at around 36 through to 1880.49 While the overall population of Europe more than doubled over the nineteenth century, France’s grew by only 40 per cent. This happened despite France having one of the highest proportions of married women of any country in north-western Europe: French couples were just having far fewer children.50 The fertility decline wasn’t just among the richest classes, but across society. In France, most peasants owned their own land, in contrast to most of Europe. In the early nineteenth century, almost 63 per cent of the French population were landowning families (compared to only 14 per cent in Britain) and so stood to gain by limiting the number of children and thereby preventing the dispersal of their property.51

Just as France underwent a significant decline in its birth rate, another process was gathering pace in the rest of Europe, beginning with Britain.

For most of the history of civilisation, societies have faced high mortality rates, with deaths predominantly caused by malnutrition or disease. Consequently, in order to have a reasonable expectation that a least a few of their offspring would survive to adulthood, families needed to have a lot of children. These circumstances started to change in Britain from the mid-eighteenth century as the mortality rate began to decline because of greater food supply, improved public sanitation and advances in medical care. Mechanised agriculture and cheaper steam-powered transport of produce in particular improved food security. So as Britain industrialised, and its population became increasingly urban, the emerging gap between the birth and death rates produced a period of rapid population growth. This persisted until families responded to the lower mortalities by having fewer children, and the birth rate started to decline around 1880.

Britain was the first state in the world to undergo a modern, sustained population explosion, which gave it a significant advantage over its rivals on the world stage. In particular, this biological proliferation through the nineteenth century enabled Britain to export significant numbers of settlers to its overseas colonies and grow them rapidly without depopulating the homeland.fn3 Industrialisation, trade and sea power were all important for the ascendancy of Britain into a global superpower, but the consolidation of the empire would not have been possible were it not for the demographic prowess of this small corner of Europe.52 This is in stark contrast to the Spanish Empire between the sixteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As we have seen, the Spanish had laid claim to a vast expanse of territories around the world (see page 51), but there were simply not enough Spaniards to make a lasting population impact on the lands they had conquered even after they had succeeded – unintentionally or otherwise – in wiping out huge numbers of the indigenous inhabitants.53

This transformation from high death and birth rates, through a phase of lower death but high birth rates, and finally to low rates of both births and deaths, is known as the demographic transition. Much of the rest of Europe and North America followed Britain in undergoing this demographic transition, with industrialisation going hand in hand with a spurt of population growth before families began having fewer children. But uniquely in France, the fertility rate had already declined significantly from the beginning of the nineteenth century, and France only began to industrialise in the second half of the century.54

Unsurprisingly, the issue of France’s low birth rate and relative underpopulation became a topic of public debate.55 Many warned that as France’s population diminished compared to its continental neighbours, it would become ever more vulnerable in the event of war, when more populous states would be able to field larger armies. Like Tacitus in the first century AD, the French were particularly concerned about the much higher birth rates of their eastern neighbours – the German states.

The growing German population came to surpass that of France by 1865, and five years later, France suffered a crushing defeat by Prussia, which led to the capture of Emperor Napoleon III, the occupation of Paris and the loss of the province of Alsace-Lorraine. And in January 1871, Bismarck united Prussia with a confederation of other German-speaking states, forging a new empire and creating the dominant land power in Europe. By the end of the nineteenth century, the languishing French population had plateaued at around 40 million. At the same time, the British population had quadrupled and now surpassed that of France, while the German population had surged to 56 million.56 France had completely lost its superiority of numbers. Generations of slow population growth had placed France on the back foot. The French regarded their eastern neighbour with existential paranoia: there were fears that with the continuing high birth rate in Germany the next war would be even more catastrophic than the last.57fn4

In the years of mounting international tensions leading to the outbreak of the First World War, the European powers obsessively compared their relative industrial capability and population growth, like pugilists sizing each other up before a bar brawl. Britain and France both feared a growing Germany, while Germany in turn looked nervously at the rise of Russia. In the end, it was the international crisis triggered by the assassination of the Habsburg heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (page 54), that lit the touchpaper. Germany reasoned that, since war with Russia seemed inevitable, it would be preferable to have that fight sooner rather than later – a gamble that activated a web of alliances and dragged Europe into war in July 1914.

With no significant technological disparity between the warring sides, Europe became locked in a strategic stalemate. Wave after wave of young men were sent into the meat-grinder of the trenches, and this conflict became the archetypal war of attrition. The sheer weight of numbers was paramount, with victory hanging in the balance for whoever could rally the larger population.

But the course and the outcome of the war did not depend on individual strength alone. While Germany’s large population enabled it to field great armies in the Eastern and Western theatres, Britain could muster far fewer troops from its own soils. But the nineteenth-century mass emigration across the empire meant the British received the support of significant numbers of troops from Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as well as India and Africa. And while, with a population 40 per cent smaller than Germany’s, France had a great deal to fear, it did not stand alone in 1914. Its alliance with Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan and, later, the United States ultimately swung the demographic balance. Even without the involvement of the US (whose expeditionary force didn’t begin arriving in greater numbers on the Western Front until the summer of 1918), the Allies were able to mobilise almost 38 million troops; the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary, together with the Ottoman Empire, fielded fewer than 25 million. In the end, the First World War was won by the Allied Powers through their capacity to mobilise more troops for the battlefield. The cradles of the 1890s had proved decisive in the conflict.

DEMOGRAPHIC CONSEQUENCES OF WAR

Population size, and in particular the number of fighting-age men that can be called to arms, has been of paramount importance in wars throughout history. But warfare in turn also has profound effects on demography, with repercussions for society and the economy that endure for generations.

We have already seen how the destruction wrought by rampaging armies, plundering to supply themselves or otherwise disrupting the agricultural cycle, causing famine and spreading disease can cause widespread mortality across the societies impacted. In the last century, the Soviet Union suffered a particularly severe demographic catastrophe.

In June 1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, starting what would become one of the deadliest conflicts in world history. Within the first six months, the Soviet Union had lost a huge expanse of territory – equivalent to roughly a third of the United States – and nearly five million men, as many as were in the Soviet Union’s entire pre-war army.60

Critically short of soldiers, the Soviets significantly expanded the age range for conscription, including men under eighteen and over 55.61 Overall, 34.5 million were drafted into the armed forces, nearly 8.7 million of whom died.62 The total number of deaths, of soldiers and civilians combined, suffered by the Soviet Union during the Second World War is estimated to be around 26–27 million – around 13.5 per cent of the total pre-war population.63 By comparison, the total number of casualties suffered by Germany amounted to 6–9 per cent of its peacetime population, and France and the UK each lost less than 2 per cent.

Alongside the immediate loss of life, the war’s additional demographic impact was a crash in the number of babies born in the Soviet Union throughout the 1940s. Demobilisation and the return of the surviving soldiers to their homes took up to three years from the end of the war. The birth rate collapsed from 35 births per 1,000 people in 1940 to just 26 in 1946. This 25 per cent drop meant that an estimated 11.5 million babies were not born over these years due to the disruption of the war,64 although the birth rate started to pick up again afterwards. The impact this had on the population structure in the Soviet Union was profound.

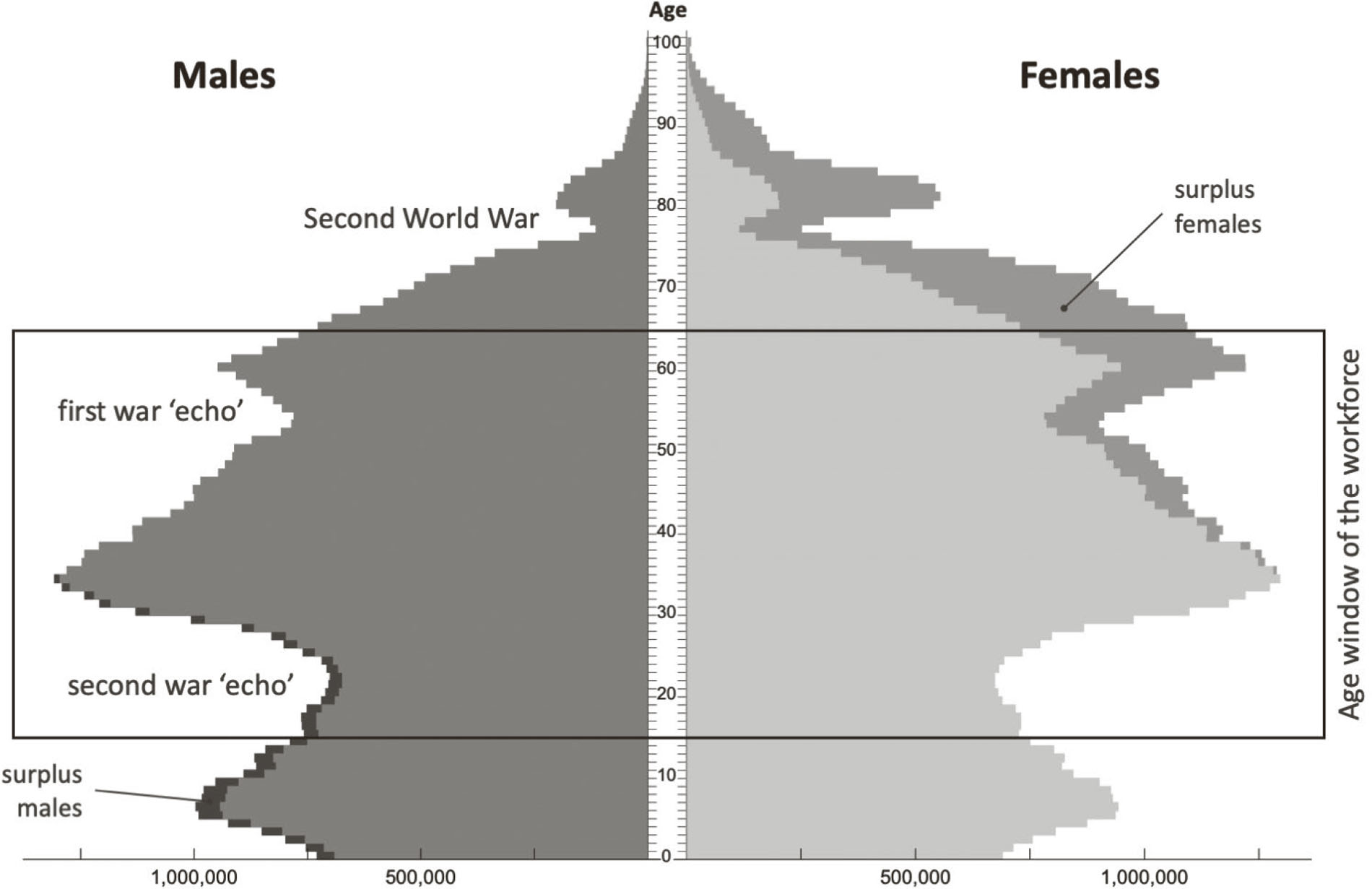

A common method for visualising a country’s population structure is known as a population pyramid. A stack of horizontal bars represent the numbers of males and females in different age ranges, running from newborns at the bottom up to the elderly at the top. When a population is growing – when there are more babies being born than there are people dying – the society is youthful and the bar graph takes on the shape of a pyramid, hence the name ‘population pyramid’.

The effects of both the cataclysmic number of deaths and the falling birth rate during the Second World War left an unmistakable imprint on the Russian population pyramid. The bars from the war years are markedly shorter, especially on the left side, where the male population is represented. In fact, the Russian population pyramid today shows a distinct pattern of shorter bars recurring roughly every 25 years – the approximate generation span. These are the demographic echoes of the devastation of the war. It shows that when the greatly reduced cohort of people born during and immediately after the war grew up and had children of their own, fewer children were born around 1968; and they in turn produced reduced numbers of offspring around 1999. The recurring demographic dent broadens each generation due to the spread in the ages at which people reproduce.

This wave-like structure of the Russian population pyramid – far more pronounced than any other nation impacted by WWII – has also affected Russian economics. Over time, as these waves progress upwards through the pyramid (as the population ages), the succession of peaks and troughs passes through the age window of the workforce – roughly those between 15 and 65 years old. A major factor in the economic strength of a nation is called the dependency ratio – the balance between the fraction of the total population that is working and paying tax, and the number of dependents, the retired and children who are instead being supported. A high dependency ratio places a greater burden on the economy and reduces productivity growth. Because of the demographic reverberations of WWII, this dependency ratio has over the past 75 years fluctuated far more in Russia than elsewhere in the world, as either more peaks or more troughs in the population pyramid pass through the working-age window. Between the mid-1990s and late 2000s, the dependency ratio decreased significantly – the bulges in the population pyramid were moving through the working-age window – which is believed to have been a substantial contributing factor to the boom experienced by the Russian economy over this period. The World Bank estimated that nearly a full third of the growth in Russia’s per capita GDP over this time was down to this demographic effect.65

But now that dependency tide has turned again, as instead more troughs pass through the working-age window, and the ratio is expected to increase significantly up to the early 2030s – more so than other nations experiencing a rising dependency ratio – placing increasing strain on the Russian economy.66 So the particular features of the age distribution of the post-war Russian population continue to have a defining influence on the economy.

One particular subset of the demography is hardest hit by war – the young to middle-aged men predominantly marshalled to fight and die in the armies. Indeed, although the Second World War exacted a devastating toll on the Soviet population overall – killed by the Nazi occupiers or succumbing to the widespread malnourishment and disease – around 20 million of the 26–27 million deaths (75 per cent) were male, and most of these men were aged between 18 and 40.67

This removal of young men from the population severely distorts the sex ratio. Most animal species naturally have populations with an even balance of males and females. Although there might be an evolutionary advantage to an individual’s genes by producing mostly sons – because, as we saw in Chapter 2, a male has the potential to produce far more offspring than a woman – in the next generation, now dominated by males, there would be a clear mating advantage to being one of the few females. So producing an equal number of males and females is known as an ‘evolutionarily stable strategy’.68 Human populations are also normally composed of a relatively even ratio of males to females.fn5 Overall, at present, the global population is around 50.25 per cent male and 49.75 per cent female.70 But on a regional level, extreme events can severely distort the 1:1 ratio – with long-term effects for society.

The jolt to the sex ratio in the Soviet Union from the Second World War was among the most extreme experienced by any country in the twentieth century. The sex ratio in the USSR prior to 1941 was already less than 1 due to the male death toll during the First World War, the revolution of 1917 and the civil war that followed. But the catastrophic losses during WWII skewed the ratio even further, especially in the western regions of the USSR where the fighting was most intense and the greatest casualties were sustained.71 In the twenty years between the beginning of the war and the first post-war census in 1959, the number of draft-age men in the USSR had plummeted by more than 44 per cent, leaving 18.4 million more women than men in that age group.72 This pushed the sex ratio down to as low as 0.64. The USSR was a country of women.

Many women had lost their husbands during the war, and with such a skewed sex ratio the prospects of finding a man to remarry, or for those never wed to find a partner, were dim. A long-term consequence of the scarcity of men, however, was a shift in male behaviour surrounding sex and marriage in the USSR. We’ve already explored humans’ in-built predisposition to form strong-pair bonds for child-rearing, which formed the foundation of the cultural institution of marriage. But the reproductive strategies of men and women are not perfectly aligned. As men are not biologically bound to offspring in the same way the mother is, it pays for a woman to be choosy over potential mates. Her interests lie in selecting the best possible partner in terms of attributes such as genetic fitness, resources and social status, as well as commitment to co-rearing the child – a strategy that prioritises quality over quantity of mates. A male, on the other hand, has in theory no major limitation on the number of children he is able to sire and so may maximise his reproductive output by having children with many different women – if he can get away with it. This conflict between male and female reproductive strategies becomes all the more pronounced in a population with a grossly imbalanced sex ratio such as the post-war USSR.

In crude terms, the dynamics between male and female in mating or marriage are those of a marketplace, subject to the laws of abundance and scarcity, supply and demand. In a population where women are in short supply, they have greater bargaining power in the marriage market, and can take their pick of husband. And because the male is unlikely to find opportunities elsewhere, it’s in his interests to remain committed to the relationship. In populations where there is a significant surplus of women, however, these priorities reverse. Women are in a weaker position to demand, and ultimately secure, male commitment and high levels of paternal investment in the rearing of offspring.73 The scarce men have less incentive to commit to relationships and less fear of the consequences of seeking liaisons elsewhere, and there are plenty of other women willing to have a child out of wedlock.74

The missing generations of men in the post-war Soviet Union therefore drastically altered the market conditions. The sociological repercussions were clearly evident in the 1959 census: fewer women were married, and the divorce rates were significantly higher. The number of marriages with a large age gap between bride and groom had increased. And far more children were being born out of wedlock.fn6

The consequences of war-induced shortfalls of men were also evident in Germany after the Second World War. Although the fraction of men killed was much smaller than in the USSR, women in their prime fertility years aged between twenty and forty still outnumbered men in the same age bracket by a factor of ten to six in 1946. Here, too, many women struggled to secure husbands and remained unmarried.75 Fertility rates dropped, and the share of children born out of wedlock more than doubled to over 16 per cent. The southern German state of Bavaria, with a predominantly Catholic population, recorded as many as one in five babies born out of marriage, probably higher than any other European region in the twentieth century.76

Thus the devastating loss of men in the USSR and Germany in WWII produced a profound and persistent distortion in the sex ratio; even today, the ratio in Russia is 0.87.77 This demographic shock had not only significant consequences for the birth rate but drove a shift in behaviour regarding sex and marriage and even changed attitudes towards gender roles. While in Britain, the US and elsewhere, female empowerment and greater financial independence brought by wartime mobilisation was short-lived, as societies and economies returned to peacetime norms and traditions,78 the surplus of women in the USSR led to long-lasting progressive cultural changes in attitudes towards divorce, childbirth out of wedlock and premarital sex.79

STOLEN GENERATIONS

War is not the only human horror that can significantly distort the sex ratio in populations.

From the early sixteenth through to the mid-nineteenth century, around 12.5 million Africans were captured and forcibly transported across the Atlantic to the Americas to labour in the plantations of European colonies.fn7 Almost two million of them did not survive the horrendous conditions of the oceanic voyage, and millions more would have perished in the raids and wars in their homeland and during transport to the coastal factories where they were sold to European slave traders (numbers that aren’t included in the shipping records). There were other trade systems – the trans-Saharan, Red Sea and Indian Ocean slave trades – which, although less significant in scale and historical consequence, together exported a further 6 million people.80

The slave trades, an abhorrent stain on human history, have had profound long-term consequences for Africa. Across large areas of the continent, for hundreds of years Africans lived in fear that they or their families could at any point be seized into slavery. The removal of large numbers of people slowed population growth. Many factors can hamper population growth, including endemic diseases, crop failures and famine, but the demographic impact of the transatlantic slave trade – in terms of the staggering numbers of enslaved people, across a huge geographical region, over a long span of time – has no parallel in human history. The estimated population of sub-Saharan Africa in the early nineteenth century was about 50 million people; without the slave trades, historians have argued, it would have been 100 million.81fn8

Alongside the overall suppression of the population growth rate, the transatlantic slave trade also had a more specific impact. The demand driving the transatlantic slave trade was predominantly for the plantations in the American colonies. Plantation owners sought fit, strong labourers, and this meant that a peculiar characteristic of the transatlantic route – in contrast to, say, the Indian Ocean slave trade, which also sought female domestic maids and concubines – was a pronounced preference for male slaves. European slavers aimed at exporting twice as many men as women from Africa, and records show that the ratio of male to female slaves transported over the duration of the transatlantic slave trade stood around 1.8:1.87

Those regions most heavily targeted for slavery experienced a significant shortage of men.88 At the peak of the transatlantic slave trade, at the end of the eighteenth century, there were fewer than 70 men per 100 women in West Africa. In Angola, the hardest hit area of the whole continent, the sex ratio dropped to as low as 0.5 or even 0.4.89 Numerous communities found themselves with twice as many women as men.

Such severe distortions to the natural sex ratio drove a shift in family structure and altered the division of labour in society. Women had to substitute for the missing men and assumed the activities and responsibilities that had traditionally been the preserve of males in agriculture, commerce and even the military. They also adopted positions of leadership and authority in their communities.90 This in turn changed the cultural norms and prevailing attitudes about the roles of women in society.

After the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in the nineteenth century, the worst-affected areas began to return to a natural sex ratio of around 1, a balanced mix of male and female. But modified attitudes and practices around gender roles continued, and continue even to this day. With cultural norms passed down from parents to children, they persisted long after the disappearance of the demographic conditions that originally gave rise to them.

In the areas of Africa that endured the most intense burden of the slave trade, women today are more likely to be employed in the labour force, where they are also more likely to have a high-ranking occupation. Both men and women in these areas display more equal attitudes to gender roles, are less likely to accept domestic violence against women and are more supportive of gender equality in public office and politics.91

Importantly, these long-term social consequences of a skewed sex ratio are only found in the African regions most severely affected by the transatlantic slave trade: predominantly western Central Africa (especially Angola), sub-Saharan West Africa and, to a lesser extent, Mozambique and Madagascar on the south-eastern coast. Yet in East Africa, where the Indian Ocean slave trade captured more even numbers of men and women, there was less of an impact on the sex ratio, and cultural norms didn’t change significantly; there’s no evidence of increased female labour force participation, for example.92

Today, these regions also exhibit the greatest prevalence of polygyny.93 It seems that the skewed sex ratios encouraged men to take multiple wives and women to accept the arrangement. And so the differences in demands serviced by the transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades may also explain why polygyny is much more prevalent in West Africa than in East Africa.94 But the long-term repercussions of the demographic disturbance perhaps extend further.

Along with promiscuous forms of sexual behaviour, the practice of polygyny can drive the rapid spread of sexually transmitted infections such as HIV/AIDS, especially if the partners are unfaithful outside their relationships. There’s not only a higher incidence of polygyny in West Africa but more infidelity by wives dissatisfied with their marriages. In this way, higher rates of HIV infection, particularly among women, across West Africa today may be driven by variations in sexual behaviour deriving from the grossly skewed sex ratios created by the transatlantic slave trade.95, 96

IT’S RAINING MEN

Circumstances that create demographic distortions in the opposite direction, to a high sex ratio with a surplus of men, are much less common, but there has been one prominent example.

In the decades leading up to the American Revolution, Britain was transporting around 2,000 convicts every year to its colonies in North America.97 Overall, around 60,000 Britons were banished there98 for crimes as trivial today as shoplifting and poaching or as bizarre as consorting with gypsies, using contraception and impersonating a Chelsea Pensioner.99 But with the outbreak of war with the American colonies in 1776, this traffic came to an abrupt halt. British jails were soon filled to bursting and, judging it to be cheaper to transport convicts overseas rather than build more prisons, parliament became desperate for some other dumping ground for the nation’s undesirables. The solution was to be found in a land on the other side of the world.

By 1770, Captain James Cook had charted the east coast of Australia and claimed half of the landmass for the British crown. Parliament now spotted an opportunity: not only could transportation to Australia serve as an emptying ground for the jails and a harsh deterrent to other criminals, but the convicts could form the vanguard of a new focus of colonisation in the southern hemisphere, supplying the labour needed to get the settlements established. In January 1788, the First Fleet arrived and established a settlement at Sydney Cove with around 1,500 settlers, 778 of whom were convicts.100 The British colonisation of Australia had begun.

The numbers of convicts sent to Australia increased dramatically after the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, peaking in the 1830s when around a third of those found guilty in Britain’s county courts101 were sentenced to transportation and several years of indentured service. This practice of forced migration began tapering off in the following decade, however, with intensifying protests against the transportation system; and the last convict ship arrived in Australia in 1868.102 By this time, over 157,000 convicts had been transported to Australia – mostly to the penal colonies established in New South Wales and the island of Tasmania – and 84 per cent of these were men.103 Even when settlers began to come of their own free will from the 1830s, the number of men arriving in Australia still vastly exceeded women, not least because the available opportunities for work were mainly within arduous occupations like agriculture and mining.

The women living in Australia – whether emancipated ex-convicts (the sentence of indentured labour was generally seven years), free migrants or those born there – found themselves in an environment with a starkly skewed sex ratio. For a long period of Australian colonial history, the average ratio was about three men for every woman; it could be as high as 30:1 within some penal colonies.104 Colonial Australia was, for almost 150 years, a land where it was continually raining men. The sex ratio didn’t reach parity until around 1920.

Consequently, the value of each woman was of course much greater than in a balanced population, and a man would be exceedingly lucky to find a wife. It was very much a seller’s market for the women. And this was significant for both sexes.fn9

Historical records show that during the colonial period, Australian women were much more likely to marry, and less likely to divorce, than their contemporaries in Europe. There is evidence that in populations with a surplus of males, the men are greatly incentivised to commit to any relationship they can secure without engaging in extramarital liaisons. They also dutifully participate in more childcare and make sure their wife is well provided for, so she has no cause to seek another husband. As a result, women in Australia felt no need to work and instead remained at home.105fn10

These male-biased conditions in colonial Australia have created enduring effects within society. What’s astonishing is that even a century after the sex ratio balanced out to parity, the enhanced bargaining power of women is still imprinted on the expectations of gender roles and the statuses of men and women in society.

In areas of Australia today that historically experienced very biased sex ratios from the penal colonies, such as the region surrounding Sydney, along the north coast and on Tasmania, both men and women are more likely to hold conservative views on the role of women within society and to expect them to stay at home. Here, women still participate less in the labour market, work fewer hours, hold more part-time positions and are less likely to be in high-ranking occupations, compared to women in areas that were not so male-biased in the past. However, they do not spend more time on household chores or childcare instead; if anything, they spend less time on such activities. This means that women living today in areas that were once heavily male-biased enjoy considerably more leisure time over the week.108

Large-scale features of human populations – such as growth rate, population size and sex ratio – have had profound effects through history. These include the spread of agricultural communities, military might and war between states, and long-lasting social changes and impacts on economics. Another fundamental aspect of human biology is our predilection for consuming substances that alter our conscious experience. In the next chapter we’ll see how, by changing our minds, such psychoactive substances came to change the world.